The news of President Biden’s ban on the importation of Russian-made ammunition sent shock waves through the gun owner community. At a stroke, up to 40-45% of the ammunition sold in the US will no longer be available. That includes ammunition not just in former Soviet bloc calibers such as 7.62×39 and 5.45×39, but also 9mm Luger, .223 Remington, and .308 Winchester.

While US manufacturers and other foreign manufacturers may eventually fill the gap, it will take months or even years before manufacturers have caught up to current ammo order backlogs and retooled to support the market. In the meantime, many shooters will be left high and dry.

An increasing number of American gun owners now realize that if they want to be able to shoot, they need to be able to provide themselves with their own sources of ammunition. And that means that they’ll have to learn how to handload.

Handloading ammunition can be a fun pastime, an adjunct to shooting. And the results of handloading can be quite rewarding, with lower cost ammunition, better accuracy, and fine tuning for your specific firearms that can surpass anything you can get from mass-produced factory ammunition.

If you’re new to handloading, we’re going to start a 4-part series on handloading, as follows:

- The Basics of Cartridge Reloading

- The Basics of Pistol Handloading

- The Basics of Rifle Handloading

- The Basics of Shotshell Handloading

To start off this series, let’s discuss what exactly handloading is and how it’s done.

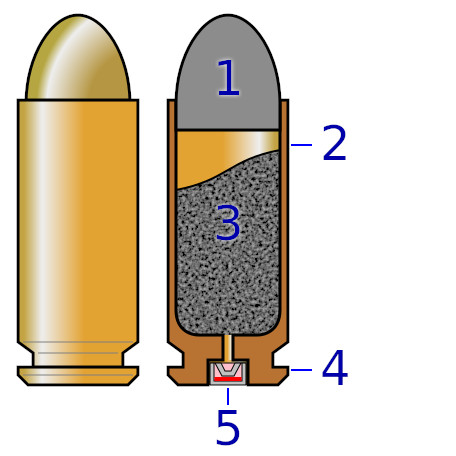

Cartridge Construction

Image: Wikipedia

Most cartridges today feature five primary components:

- Bullet

- Cartridge case

- Powder

- Rim

- Primer

Most firearms today, aside from those in rimfire cartridges in .22LR and other rimfire calibers, are chambered in what’s known as centerfire cartridges. That means that they feature a case made of brass, or less commonly steel or aluminum, with a primer in the center of the base of the cartridge. In the case of shotshells, the shell can be made of plastic, waxed paper, brass, or sometimes even aluminum, most often with a brass-colored steel base.

Centerfire cartridges function by a striker or firing pin striking the primer, which contains a minute amount of an explosive compound. The strike on the primer causes a flash of sparks that ignite the powder inside the case. The powder begins to burn, raising pressure inside the case. The case seals against the chamber of the firearm, and the rising pressure forces the bullet (or shot) down the bore of the firearm.

Once you’ve fired your cartridge, the operation of the bolt will cause the extractor to pull on the case rim, extracting the cartridge from the chamber.

When handloading or reloading ammunition, the basic steps you’ll take are to insert a primer into the case, fill the case with powder, then insert the bullet. Then you have a completed cartridge. Let’s take a closer look at the construction of a cartridge, but first an important rule about safety.

SAFETY WARNING: Handloading ammunition is an inherently risky endeavor. Failure to engage in safe practices can result in severe injury or even death. Do not attempt to load ammunition without being prepared, which includes reading and watching videos about proper reloading safety practices.

Do not eat, drink, or smoke while handloading. Do not handload near open flames, pilot lights, or heat sources. Wash your hands thoroughly after handling bullets, powder, cases, or ammunition.

Use published load data and do not stray from published data unless you are an expert, using software like Quickload to assist you, and are willing to take the risk of blowing up your guns.

Handloading can be a fun hobby and very rewarding, but getting distracted, failing to heed safety warnings, or using the wrong powder can result in severe injury or death. Do not tempt fate: always err on the side of caution.

1. Bullets

For the most part, handloaders are going to be using copper-jacketed lead-core bullets, just like the type they’re most used to getting in factory ammunition. Non-lead bullets such as brass and copper are gaining in popularity, and are required in some areas. And lead bullets remain popular with those looking to shoot cheaply.

The number of choices you’ll have available to you will far exceed what you can get from run of the mill factory ammunition. But it’s important to remember that you have to use the proper load data for the bullet you’re using. Just because two different bullets each weigh the same doesn’t mean they use the same load data. One bullet may be longer than the other, and the longer bullet, seated to the same length with the same amount of powder, will cause higher pressure.

2. Cartridge Case

Image: Wikipedia

Centerfire cartridge cases today are made with two types of priming systems, Berdan and Boxer. The Boxer case and priming system was invented in Europe and is now most commonly used in the US. The Berdan system was invented in the US and is now most commonly used in Europe, particularly with military ammunition and steel-cased ammunition.

For our handloading purposes, we are going to discuss brass-cased, Boxer-primed rifle cartridges, and Boxer-primed shotshells.

Aluminum cases are one-time use. Steel-cased ammunition can be reloaded, albeit with great difficulty, and it’s not worth the effort to do so unless you live in an area like remote Africa or Asia and all you have is steel cases. Berdan-primed cases can also be reloaded, but also with greater difficulty, and Berdan primers are difficult to source.

The centerfire Boxer-primed brass case has taken over the market because of its ease of reloading. The Boxer priming system features a single flash hole right in the center of the case head. That makes it incredibly easy to remove the primer by running it into a die that features a decapping pin that pops the primer out. Berdan cases feature two flash holes on either side of the center of the primer pocket, making it impossible to remove the primer with use of a die.

Brass cases can also be long-lived. If you take care of your brass, never oversizing or overworking it, keeping pressures to reasonable levels, and occasionally annealing necks and shoulders when necessary, you could use a single case 10-20 times or more before replacing it. With cases being the most expensive part of a piece of loaded ammo, that can significantly reduce the cost of each piece of ammunition that you load.

3. Powder

Smokeless powder comes in a wide variety of burn rates, from very fast burning powders intended for use in pistols and shotguns to very slow burning powders used in large, powerful rifle cartridges. Don’t assume that you can substitute one powder for another, such as Reloder 7 for Reloder 17, or even Accurate 4064 for IMR 4064. Using the wrong powder can be dangerous. There are three primary issues that come up when it comes to improper use of powder.

a. Improper Substitution

Substituting a powder improperly can result in using a powder that is too fast when a slower-burning powder is called for. That can raise pressures to unsafe levels, leading to a gun blowing up.

b. Double Charge

Many shooters like to economize, using small charges of fast-burning powder when loading pistol rounds. That raises the likelihood of an accidental double charge, which could also lead to a catastrophic breakup of your firearm and severe injury. You can counteract that by sticking with slower-burning pistol powders or double- and triple-checking each case you load.

c. Unknown Powder

Never ever leave powder sitting out in a hopper or reloading scale. And never transfer powder permanently from its original container into another container. You may think you know what powder you’ve left out, but you won’t know for sure. Particularly when it comes to ball powders, many powders look a lot alike.

You may think you left Accurate 2520 in your powder hopper when loading for rifles. But if you accidentally left Accurate No. 2 in the hopper and try to load rifle cartridges, you’ll be lucky to live.

The name of the game when it comes to handloading is safety. Don’t cut corners and don’t think you can make substitutions or change loading parameters without consequences. Learn as much as you can before making the jump into handloading.

4. Rim

Most cartridges today are what are known as rimless cartridges, meaning the rim is the same diameter as the case head. This eases cartridge feeding in both bolt action and semi-automatic firearms. Rimmed cartridges have a case rim that is significantly wider than the cartridge case head.

For the handloader, this doesn’t mean much aside from making sure that you use the proper shellholder for each caliber you reload.

5. Primer

There are two major diameters of primer, large and small, and four primary sizes: large pistol, large rifle, small pistol, and small rifle.

These primer sizes are not interchangeable. While you can fit a large pistol primer into a case that takes a large rifle primer, the primer height is different and can result in a misfire. Similarly, a large rifle primer in a large pistol case will sit too high and could lead to misfires, slamfires, or jams.

There are also magnum versions of primers, such as small pistol magnum and large pistol magnum, intended for more powerful cartridges such as .357 Magnum or .44 Magnum. There are benchrest versions of rifle primers, intended for competition shooters who need maximum consistency in primer ignition. And there are military primers intended for use in handloading 5.56mm NATO, 7.62x39mm, and 7.62x51mm ammunition.

Always be aware of the type of primer called for based on the cartridge you’re loading and the case you’re using.

In the case of shotshells, you’re likely going to be using 209 primers, or in the case of some brass shells, large pistol magnum. Not all 209 primers are the same, and there can be significant differences among various manufacturers. Don’t assume that a Cheddite primer can be used when a Winchester is called for. Always look for specific load data for the primer manufacturer you’re using.

Load Data

If you’re starting out handloading, it’s best to stick to published load data. Once you get some experience under your belt, you can think about playing around with unpublished recipes, different powders, or loading for obscure cartridges with little load data around. But jumping in too soon when you’re a beginner is a recipe for injury.

Some bullet manufacturers often provide limited load data for their bullets online, as do most major powder manufacturers. That will get you only so far, however, so it’s a good idea to get some physical reloading manuals. The newer the manual, the more reliable the information, as formulations of powder can change over time, meaning that data that’s more than 10-20 years old could be outdated and even dangerous.

Most reloading manuals also have great introductory sections with far more information than contained in this article. Do yourself a favor and read that information carefully and thoroughly. It can seem overwhelming at first, particularly if you’ve never read anything about handloading before, but it’s well worth the effort. You can never be too safe.

The Tools You’ll Need

Like many other hobbies, handloading requires specialized tools. Among those you’ll need are:

- Press

- Dies

- Priming Tool

- Scale

- Other Accessories

1. Reloading Press

Reloading presses run the gamut from small presses you can fit in your hand all the way up to automated cartridge loading machines. For most beginners, you’ll want to start out with a single stage press. Even here you have a number of options.

Among the most popular is the RCBS Rock Chucker, which can even come as part of a reloading kit that contains all the tools and accessories you need to get started. Similar presses and kits come from competitors such as Lyman, Redding, Hornady, and Lee.

Shotshell reloading requires specialized presses, ranging from basic presses such as the Lee Load All up to specialized and expensive presses from MEC, the primary manufacturer of shotshell reloading presses.

2. Dies

If you’re loading pistol and rifle cartridges, you’ll need dies to load your cases. Most die sets for pistol calibers come as part of a 3-die set, while rifle calibers normally come with a 2-die set. Rifle die sets contain a sizing die, for resizing brass that has been fired, and a seating die, for seating bullets in the case. Pistol die sets contain a sizing die, an expander die to expand the case mouth to accept bullets, and a sizing die that often doubles as a crimp die to crimp bullets in the case.

3. Priming Tool

Many presses will contain some sort of priming attachment to seat primers in the case, or can have automatic primer feeding added in some way. But if you’re just starting out, it’s often better to use a hand priming tool. Those from Lee and RCBS are among the most popular.

4. Scale

While there are ways of measuring powder volumetrically, either through the well known Lee yellow powder scoops, or bench- and press-mounted powder measures, you’ll achieve better accuracy when weighing your charges of powder.

Most beginning reloading kits come with a balance beam scale, which can be very accurate, although slow to use. Electronic scales are growing in popularity, particularly those from RCBS, Lyman, or Hornady that are attached to an automatic powder measure. These can greatly speed up the reloading process, although electronic scales can drift over time.

5. Other Accessories

There are numerous other accessories that can help with the handloading process, such as cartridge loading trays, cartridge trimmers, case prep tools, etc. Once you start learning how to handload and get used to the process, you’ll be able to assess which of these accessories can help you in your handloading.

The Handloading Process

The basic process of handloading is the same for pistol, rifle, and shotshell. You’ll start with a case or shell. If you’re using brass that has already been fired, you’ll need to resize it first in a sizing die, which normally contains a decapping pin that will remove the old primer. Rifle brass will need to be lubed before sizing, while straight-wall pistol cartridges don’t need lube when using carbide sizing dies (which most pistol sizing dies are). Occasionally you’ll need to size virgin brass, especially if case mouths have gotten dinged or dented in shipping.

Once your cases are sized, you’ll want to check to make sure that they don’t exceed the maximum case length for the cartridge you’re loading. Then you’ll prime the case and add the correct weight of powder, based on the load manual you’re using. Finally, you’ll seat the bullet to the proper overall cartridge length, and crimp the bullet if needed.

As has been stated before, safety is paramount. Read loading manuals, reloading guides, and anything else you can get your hands on. If you always remember to practice proper safety precautions, handloading can be a very rewarding hobby.